The Economy, Markets, and Profitable Insights

(How to More Effectively Put the Odds of Investment Success in Our Favor)

Introduction.

My Simple Two-by-Four Approach.

What We Will Need To Play This Game.

The Big Picture.

The Economy.

The Business Cycle.

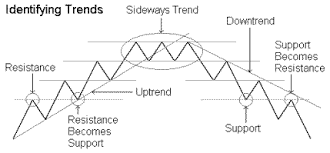

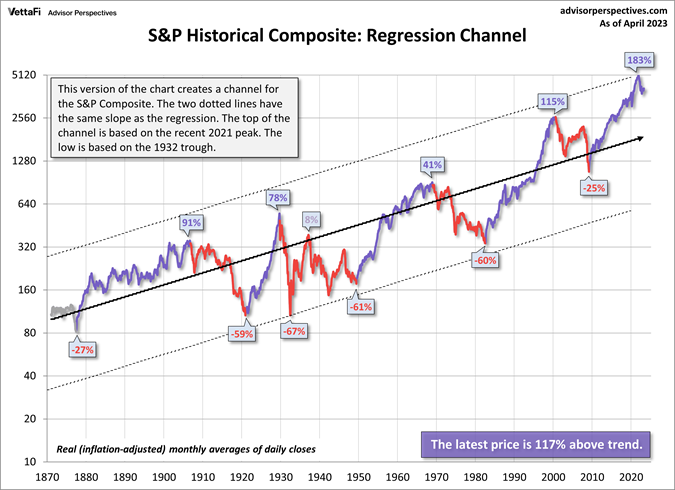

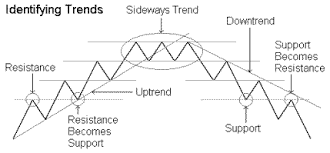

Seeing The Market's Big Picture.

Three Classic Trading Strategies.

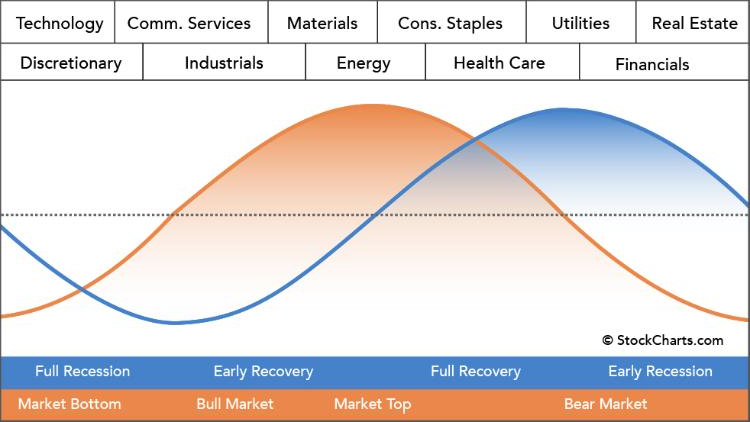

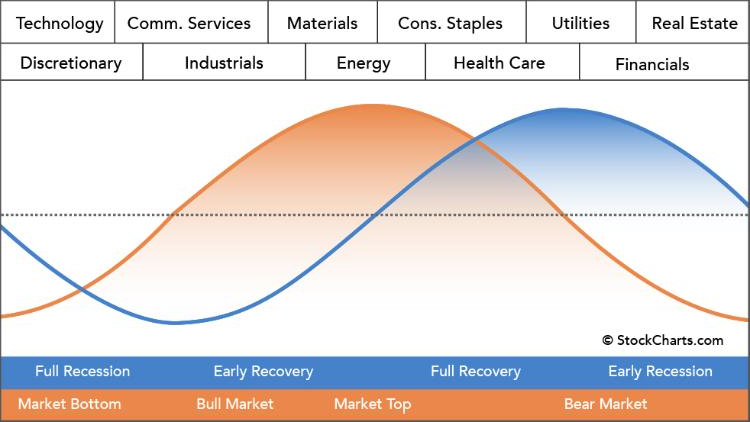

A Closer Look At Market Cycles.

Investment Wisdom.

A Closer Look at Miscellaneous Bits of Investment Wisdom.

Summary.

— Introduction —

If you are like me,

you've grown up in a place and time where society

has encouraged us to get a good education, to work hard, and to play by the rules.

We're told, if we do this, we should be able to get a good job.

Having a good job enables us to purchase the goods and services that

we're conditioned to believe that we need to be happy and live

The American Dream.

We're also told to save and invest some of our earnings to meet our future needs,

like buying a house,

sending a child to college,

to buy a farm, a ranch or some other type of dream business,

or to just achieve Financial Freedom

(i.e., to be able to retire).

Starting or owning a small business is one way to invest for the future,

but this approach is no slam-dunk guarantee of success.

In fact, most small businesses fail.

Alternatively, we can invest in our education and skills;

and historically speaking, this approach has always paid attractive dividends.

But if we ever want to stop working, we still need a way to save for retirement.

Society says we need to turn to the banking system and Wall Street.

The big problem with simple bank savings accounts, money market accounts and most CDs

is that the rate of return almost never exceeds the rate of inflation after taxes.

Sure, our savings will be safe

(at lease safe to the FDIC Limit),

but we will still lose purchasing power over longer periods of time.

So, that leaves Wall Street,

which often panders to our natural Lottery-Ticket mentality —

we all want to get rich quick without having to investing too much time, money or effort,

which is an approach that almost never works in real life.

Conversely, getting rich slow-and-steady does work, and almost anyone can do it.

Most start by investing in the latest hot (five star) fund or stock,

only to find that they are buying-in near the top.

That's what happened to me, and many others like me.

Often, the only reason my investments were getting bigger was because I kept adding new money every month;

and if I stopped adding money, I often found the value of my investments going down.

It is not uncommon for new investors to find themselves

buying high and selling low,

the exact opposite of what we should be doing.

Many give up, thinking "This game is just rigged against me."

I did not give up, thinking "Others I've met were able to do this and I was going to figure it out."

In time, I was able to figure out that much of what we're told and believe about trading and investing on Wall Street is just plain wrong

or simply wrong for us in our particular situation.

There's a reason why The Smart Money (the pros) make money on Wall Street off the backs of,

well let's just say,

not yet smart money.

In this paper, I explain what does work and why,

and what we need to know and do to more effectually grow our savings to meet our future needs.

— What We Will Need To Play This Game —

There are a number of things we will need to have and know to be effective (to earn money) in this Wall Street Markets (trading and investing) game.

-

Wall Street Markets are primarily a mechanism designed to fund economic opportunities,

to enable saving for the future, and to diversify risk.

When a business (or one or more individuals) have a profitable idea that requires public funding,

they tend to take their plans to one or more of the big investment banks

(many have or had offices on or around

Wall Street,

and that's why the term Wall Street is now a metaphor for all the individuals and businesses

that can legally operate to profit from the normal operation of our global financial markets).

These banks and related participants can help them issue equity

(stock)

and/or debt (bonds)

to raise the capital that they need via an Initial Public Offering (IPO).

In business and finance,

the term Capital means the money desired to pay for real property (e.g., office, plant and equipment) and

intellectual wisdom and ability (intangible property) needed to start and operate a business venture.

The other term often heard in this context is Labor,

which is actually one of many resources (variable costs) going into the business to yield the presumed

valuable products and/or services

to be sold by that business to earn a profit,

a rate of return on that investment.

Once issued, these investable securities (legal claims against the issuer)

are free to trade in the U.S. on SEC

Regulated Markets

(a.k.a., The Markets),

thus allowing all savers to both invest in future economic growth

and to diversify their risk exposure

by owning a basket of dissimilar investments.

Investors that buy stock

are taking an ownership interest in the issuing business.

These equity owners are entitled to a proportional stake in the future growth and earnings of that business,

which can result in price appreciation of the stock; and

some of the resulting earnings that can also be paid out as dividend income.

Investors in bonds are basically making a loan,

normally for a fixed period of time,

and they will earn interest income until that loan is repaid.

Government entities also issue bonds to raise capital to fund their new projects and continuing operations.

The financial industry has also created an amazing number of derivative securities (e.g., options),

the value of these derivative securities is based on the value of the underlying basket of Stocks, Bonds or Futures

plus some number of financial factors that make them unique and presumably useful.

It is best to master the underlying securities before investing any time and money in these tradable derivatives.

I can assure you that if you are unable to be a Consistently Profitable Trader (CPT)

with one or more of these basic securities types,

you are not likely to be a CPT when the investment calculus is complicated one or more new dimensions,

like time (when you add an expiration date, you change the profit target from sooner or later

to must see and take a profit before the expiration date or accept a guaranteed loss).

Generally speaking, most derivatives are just not for beginners.

However, there is one other type of derivative that is well worth our time

and a great place to start.

There are many businesses on Wall Street that are in the business of investing

Other People's Money (OPM).

They are Regulated Investment Companies (RICs)

and they issue shares that have ticker symbols just like other stock companies,

and about half of these shares trade all day long just like other stocks and bonds

and can distribute periodic cash payments just like some other stocks and bonds.

The other half only trade once a day, at the next 4 pm closing price.

Most people know of these RICs by their generic street name, Mutual Funds.

All of these funds are professionally managed, and they allow investors to participate

in the growth of our economic system without having to bear the risks associated with individual stocks and bonds.

It is best to focus the bulk of your time and capital on a few dissimilar investments that are very likely to survive,

that will pay a market rate of return to hold, and that are very likely to see higher prices sooner or later.

All of the securities introduced above can be bought, held, and sold in a

properly funded and permissioned brokerage account.

To learn more about the operation, history, and strengths and weaknesses of Wall Street,

consider William Cohan's book Why Wall Street Matters.

Warning: There are two less noble secondary purposes for the existence of Wall Street markets.

These markets allow Wall Street professionals to get access to your savings.

These professionals literally feed at your expense.

You must pay to play on Wall Street.

But you don't have to pay that much,

and thanks to zero-fee trading commissions,

you can now pay even less.

But rest assured, Wall Street professionals have many ways to feed on your hard earned savings.

Furthermore, Wall Street markets can provide a venue for individual entertainment and stimulus

(e.g., a casino).

If this is your primary motivation,

don't be surprised if it costs you money,

just like every other entertaining activity.

If you want to make money on Wall Street,

become a professional or just focus on the primary purposes bolded above.

-

Wall Street is very good at transferring wealth

from the impatient, impulsive, and uninformed to the patient and methodical.

That's why we need to understand that for the overwhelming majority,

Trading and Investing is a Loser's Game!

Charley Ellis says in his classic book Winning the Loser's Game,

"In a winner's game, the outcome is determined by the correct actions of the winner.

In a loser's game, the outcome is determined by the mistakes made by the loser."

For most people,

tennis and golf are examples of a loser's game;

the winner makes fewer mistakes or fewer than average.

There are clearly some professionals operating on Wall Street that can play a winner's game,

but most professionals and virtually all non-professionals have to play the loser's game, and

their results will very much be a function of their ability to avoid making big mistakes,

which are often caused by our impatient, impulsive and uninformed actions.

If we want to grow and keep our wealth on Wall Street,

we're going to have to get good at avoiding big mistakes

and learn how to manage the small ones that cannot be avoided

by having a patient methodology that puts the odds of success in our favor.

Authors Note: I've been doing this now for over three decades and

I know for a fact that it's not that hard to make a little money here and there, over and over again;

and all this can compound to a very considerable sum in time.

But I also have to acknowledge that all of my failures to grow real wealth have always been due to just a few BIG mistakes.

Because investing is naturally risky,

there will be losses; and not all losses can be avoided,

but most can be minimized.

The pros say that it helps to think of losses caused by normal market risks as a cost of being in this business,

a business expense that can be managed.

Furthermore, I believe that anybody can learn to make these small profits associated with small risks,

but most become impatient and take on more risk to magnify their rate of return.

Truth be told,

most of us can learn how to

get away with a little extra risk most of the time.

Some of us can actually get good at managing bigger risks

(i.e., learn how to play a Winner's Game).

We're all subject to a lucky streak in bull markets,

which begs the ultimate question.

"Am I clearly able to play the Winner's Game?"

Honestly, most should confess the answer is "No, my skills are not there, yet!"

Warren Buffett likes to say,

"I only have two rules."

"Rule No. 1: Never Lose Money." and

"Rule No. 2: Never Forget Rule No. 1."

It's very important to understand that money lost by the beginner version of us

cannot grow to support the retired version of us.

Ideally, we should never put on a trade that can, sooner or later, result in a big permanent loss of capital

(our hard-earned savings).

I believe this is what Warren Buffett is talking about.

We simply must avoid excessively risky trades and investments

that can easily result in a permanent loss of our savings

that need time to grow to fund our retirement goals.

We should ask,

"What's the likely average cost, worst-case cost, and what are the odds?"

(We'll talk more about how to answer these questions later.)

We only want to take on risks that are bearable and that we can manage,

risks that can be justified by likely returns

(i.e., the average loss is easily overcome by the average gain,

and the worst-case loss will never kill our account and make us start from scratch again),

because sooner or later the odds will catch-up with everyone,

and a big risk can turn into a big mistake that can wiped-out months and sometimes years of savings and compound growth.

We simply must learn how to manage the risks we take and

avoid the risks that we cannot manage or afford,

risks that can result in a big mistake.

-

We will need time, lots of it.

Compounding can do amazing things to grow wealth,

but it will take time and money.

It's earning new money (capital growth) on top of prior growth from prior savings

(the initial investment capital),

one compounding period after another.

Compounding starts slow,

but after a few decades (e.g., two to three or four, depending on the rate of return)

of continued regular savings and positive compounding,

that savings growth accelerates to the upside

and can make you truly rich,

relative to your rate of consumption and the percentage of your earnings that you are able to save

(i.e.,

learn to Pay Yourself First

by saving 10% of each paycheck and living within the other 90%).

It's never too early to start saving for retirement;

and the later we wait to start,

the more we'll have to save to catch up,

which is the only effective way to catch up

(don't make the common mistake of thinking that taking on more risk to realize a greater rate of return is the answer

as that approach tends to yield greater losses,

which makes the problem worse).

At some point,

we'll never catch up,

unless we hit the lottery

(an extremely unlikely to succeed retirement strategy,

and buying multiple lottery tickets to improve the odds is simply a voluntary tax

on those who refuse to understand the basic nature of mathematical probabilities

and how an incremental increase affects the resulting odds —

buying the first ticket takes the odds from no chance of winning to

one chance in whatever the odds are,

it's simply paying a dollar to own a now possible dream;

but buying the incremental ticket has only a negligible improvement when the odds are incredibly low,

as in the case of lottery tickets,

it's truly throwing away good money after bad).

It's amazing to me how many people come to Wall Street thinking that it's a quick and easy road to riches,

and that all one need's is a good stock tip or a small piece of the next hot ticket.

I can assure you, from first-hand experience, that this is a mistaken notion.

The only thing that happens quickly on Wall Street is losses,

which reminds me of the old saying;

"The quickest way to make a million dollars on Wall Street is to start with two million."

If you treat Wall Street like a lottery ticket, expect lottery ticket like results

(i.e., a few will hit it big, but 99.9%) will lose all or almost all of their money);

but unlike the lottery where everyone is playing the same (incredibly unfavorable) odds,

on Wall Street the odds will always favor the patient and methodical,

and those who are better prepared and equipped.

Slow and steady over time is key to winning the Loser's Game.

Unlike the lottery where just few will ever realize their desired riches and most will simply end up as losers,

a patient and methodical approach,

like what I'm presenting in this paper,

can easily enable anyone with a decent job (or some other ability to earn money like a small business owner)

to retire with the capital base needed to enjoy a retirement lifestyle similar to what they had while earning and saving.

So, start as soon as you can, be a CPT,

and allow compounding work its magic.

-

We will need investment capital, a lot of it!

It takes money to make money.

The best quality investments are naturally expensive because they are so attractive.

This is simply a fact of life.

Having investment capital is a prerequisite,

it's the price of admission to this game.

Furthermore, the more capital we have to invest,

the easier it can become to earn even more while reducing overall risk thanks to increased diversification.

Initially, commit to save 10% of your earnings and live within the other 90%.

Use the simple

Dollar-Cost Averaging (DCA) strategy

to invest that 10% in a low-cost, total market index fund to raise the initial capital base

(e.g., VBINX).

This strategy tends to yield a cost basis

(the average price per share, which is also the break-even price)

on the investment that is lower than the average price seen in the trading range of the investment over longer investment periods,

which makes it easier to harvest a positive rate of return, to be a CPT, in some future market up turn.

This approach also gives us the time we need to master the wisdom presented here.

Once enough capital is saved,

it's actually possible to just live off of the yield from U.S. Treasury Bills, Notes & Bonds,

which are defined on Wall Street as the

The Risk-Free Rate of Return.

We're talking about more than 10 million dollars

depending on current interest rates and your cost of living

or what I like to call "Your cost of happiness."

For example,

if we had $10,000,000 and invested in U.S. 10-Year Treasury Notes

yielding something like 2% (in 2016),

we'd be earning about $200,000 before taxes each year.

But note that interest rates go up and down all the time,

just like all other market priced investments;

and that's why we need to understand the markets and how to effectively select and manage our investments.

We will need to be able to handle a big, longer-term downward move,

which could seriously reduce the amount we'll have to live on.

Having a large capital reserve can greatly reduce the impact from adverse economic shocks,

another annoying fact of life.

-

We must maintain a rational Main Street mentality when operating on Wall Street.

Most people don't and as a result end up with poor investment results.

Let's consider a made-up example to illustrate the point:

Let's say that you're a newly minted college graduate and you've just accepted a decent job offer.

Your dear ol' Dad gives you $10,000 as a graduation gift, and you decide to buy a new (to you anyway) car to get to work.

You look around and find a small number of perfectly good choices and pick the best one (in your eyes).

A few days later a guy says, "Hey, I'll buy that car for $11,000!"

That would be a quick 10% profit.

Will you take his offer?

What if he had offered $9,000 (a 10% loss)?

You might say "Sure!" to the higher offer and get your next best choice

(Why not? I'm generally happy to let someone pay me $1,000 to take my 2nd best choice,

especially when the difference is small.)

or you might say "No thanks!" to both offers thinking

"I bought this car to get to work, etc. and it's getting that job done." —

most of the people I've met are busy and don't want to redo work they've already done to their personal satisfaction.

Either way, both answers are examples of typical Main Street thinking —

we're not going to jump in and out, just because the market price went up or down,

when that jump leaves us in a less favorable situation looking forward.

Now let's say that your new boss gives you a $10,000 401k contribution as a signing bonus.

Dear ol' Dad says,

"Invest that in a good Blue Chip mutual fund

(e.g., an S&P 500 Index Fund)

because they're very likely to survive and grow at an average 8% compound rate over time;

and in thirty years that 10K bonus should be worth about $100,000."

Let's say you take his advice, and after a few weeks or so

you check on the fund and notice that it is up 10% (or maybe down 10%).

Do you sell?

Believe it or not, most retail investors will hold on to the 10% gain thinking,

"I'll hold out for more of this and sell when it gets to 11% (or whatever)."; and

sell the 10% loss thinking, "I can't afford anymore losses like this."

It's important to realize that marketable investments trade up and down all the time,

and that we'll need a strategy with favorable odds to succeed (more on this later).

Ask yourself, "What's the real economic difference between these two examples?

In both cases, the underlying asset still retains the ability to meet the initially intended purpose;

and by the end of this paper, it should be clear that if you make a good purchase going in,

you should not sell for a loss just because the market now says

"Your purchase is worth less than you paid."

And in the case of the 10% gain,

it might not make sense to sell that either,

if a chuck of the profit has to go to the taxman and you don't have a better place (a plan) to invest the rest of that money.

Please understand that most of what you're going to hear from Wall Street Talking Heads (over and over again)

is just plain wrong (for you or worthless information from a practical Main Street perspective)

and repetition does not make it right (nor useful but may make it popular wisdom).

Wall Street likes to generate a lot of sound and fury

as it perpetuates its Fast Money mentality, and

this has a tendency to make us anxious and confused about what we should do next.

Just because Wall Street changed its mind about the price (perceived value) of our investment,

does not mean we were wrong to have bought that investment then,

and more importantly, that we're wrong to hold on to it now.

It is critically important that we never forget that one of Wall Street's primary motivations is

to get us (their retail customers) to buy or sell something

because every time we make a trade they get a chance to feed off our account.

When this happens, we need to turn off the TV (or whatever the source), relax and think about our real objectives,

and ask, "Does this (trade) make sense for my situation on Main Street?"

If not, why should it make sense for us on Wall Street where we have to go to buy and sell our investments?

The same basic principles of business and economics apply to both streets. Right?

(Just in case you're not 100% sure of the answer,

check-out your local or favorite university,

it does not have two different sets of classes on business, finance and retirement planning — one for Wall Street

and different set for everyone else.)

A much better set of questions might be,

"Is this investment right for my reason to be on Wall Street?", and "Does the current market price help me reach that objective?"

-

We need to understand the Market's Nature.

At the most simplistic level,

the market for investable securities trades up and down

in a range that reflects the market's view of likely future value,

which seems to change all the time.

Sometimes the market is willing to price securities at amazingly high premiums,

and at other times, at astonishing low discounts.

Consider the following from Warren Buffett

(a market perspective he got from his mentor Benjamin Graham,

author of the definitive book on value investing

The Intelligent Investor):

Mr. Market

To understand the irrationality of the stock prices, imagine that you and Mr. Market are partners in a private business.

Each day without fail, Mr. Market quotes a price at which he is willing to either buy your interest or sell you his.

The business that you both own is fortunate to have stable economic characteristics, but Mr. Market's quotes are anything but.

For you see, Mr. Market is emotionally unstable.

Some days, Mr. Market is cheerful and can only see brighter days ahead. On these days, he quotes a very high price for shares in your business.

At other times, Mr. Market is discouraged and seeing nothing but trouble ahead, quotes a very low price for your shares in the business.

Mr. Market has another endearing characteristic, said Graham. He does not mind being snubbed.

If Mr. Market's quotes are ignored, he will be back again tomorrow with a new quote.

Graham warned his students that it is Mr. Market's pocketbook, not his wisdom, that is useful.

If Mr. Market shows up in a foolish mood, you are free to ignore him or take advantage of him,

but it will be disastrous if you fall under his influence.

Mr. Buffett cautions investors to never forget that stocks are simply a fractional ownership claim on a business and

bonds are simply a loan to a business or government entity; and

the rate of return on both investments depends on:

1) how much you pay for that investment (the cost to get in), and

2) on the future economic prospects and prudence of the issuer of that security

(the tangible form of the investment).

To be a successful investor, one needs

good business judgment to understand the likely future economic value of an investment opportunity and

the ability to protect oneself from the emotional whirlwind that Mr. Market unleashes.

Benjamin Graham had another popular saying that is worth considering in this context:

The Market is both a Voting and a Weighing Machine

In the short run, the market is a voting machine; but in the long run, it is a weighing machine.

Mr. Graham is basically telling us that over shorter periods of time,

traders and investors buy and sell

based on what they think near-term future prices are likely to be,

and as a consequence actually drive near-term prices accordingly,

which can seem a little crazy relative to the underlying realities.

But over longer periods of time,

thanks to actual earnings and economic reports,

we're all better equipped to understand how well or poorly

the businesses and governments that issued our investments are in fact doing —

are they creating real economic value or not,

and are they able to make the expected future payments or not? —

and all that also drives market prices accordingly.

So, market prices both anticipate and

track the underlying economic realities of the entities that

issue those investable securities.

We can use fundamental analysis

(how the business makes money)

to understand what could be a good investment,

and when it is better to be a buyer or a seller of that good investment

(i.e., how to effectively take advantage of the Market's Nature).

Unfortunately, mastering fundamental analysis is no simple task;

it's functionally equivalent to earning an MBA

in Accounting, Finance, and Economics.

An alternative approach

(assuming we can find a good investment — more on this later),

we can use technical analysis

(use the Market's Collective Wisdom

as expressed in market prices seen over longer periods of time),

to understand when it is better to be a buyer or a seller.

Technical analysis is a skill that is much easier to master

and can also greatly improve our odds of success.

Ideally, we'd use fundamental analysis to find good investments,

and to establish good working prices levels for buying at discount prices and selling at a premium.

We can then use technical analysis to optimize our actual buying and selling — the true professional approach.

We'll talk more about all this later.

But first we must get through the following preliminary stuff.

-

We're going to need a strategy

(a methodology that puts the odds of success in our favor),

and the self-discipline to work and refine the process.

(This second part should be an iterative approach that yields incremental improvements

but be careful not to break something that is already working.

It is very easy to over optimize something for a specific market condition

only to have the market evolve to a new condition.)

We will need a set of rules for security selection and that also generates buy and sell signals.

(Getting this stuff from anybody else is just a recipe for disaster.)

The best-known strategy is simply to "Buy Low and Sell High";

and there are basically two major approaches:

- Use a Value based approach.

The basic idea is to figure out the value of something,

be a buyer at market prices below that,

and a seller at prices above.

It's a strategy that depends on us using some analytical process to establish favorable prices

(e.g., fundamental and/or technical analysis),

and then patiently wait for Mr. Market to offer up favorable prices.

This is Warren Buffett's approach.

- Use a Momentum based approach,

which is very easy to understand and a popular Fast Money strategy.

The basic idea is to trade with the trend,

Buy Winners and Sell Losers,

and that naturally causes market prices to trend further Up and Down,

which eventually creates several related cyclical patterns

(more on this later).

This is purely based on technical analysis,

which quickly leads to the idea of

getting in and out with a profit before the trend reverses.

It's a popular Wall Street strategy that depends on us being faster than average,

which is very appealing to those who believe they're better than average,

which is almost everyone before they learn the hard facts of life on Wall Street —

1) the average market participant is a professional that is way better trained and equipped than the average retail investor,

and

2) once the short-term trend is obvious to everyone,

that obvious momentum move is pretty much over and the Smart Money is getting out.

In fact, they're on the other side of the trade with the last few to get in.

This momentum-based approach can be very profitable

when a little relevant market wisdom is applied to a reasonable timeframe.

But most Newbies (the Uninformed Money) make the mistake of simplistically applying this approach to

timeframes and/or securities they are ill-prepared to trade

(we'll learn a lot more about the informed approach later in this paper).

There are a million variations on these two major strategies,

including an amalgamation of both,

and it will take some time and effort to develop (learn) a specific version (or two) that we both understand and trust.

I present some of these below,

but you'll have to master a (your) take on the process.

Be patient and persistent.

Know that it can be done.

Many others have done it and so can you!

Note that just because the guy on the other side of your trade is a pro

or a computer programmed by a team of professionals

doesn't automatically mean that you can't make money.

You can,

but not without a methodology (a systematic strategy) that has favorable odds

and the self-discipline to focus on and work to improve that methodology.

Here's my basic strategy, which has four major parts.

Part 1: Focus the bulk of my Time and Money on a few Dissimilar, Survivable Investments

that will Pay me to Hold, and that are very likely to see higher prices sooner or later.

This is a very good way to avoid a permanent loss of my savings.

Part 2: Trade with the Health of the Broader Market Trend,

an enlightened momentum approach.

Part 3: Trade like a big Value Investor.

That is, I want to only Buy at Discount Prices, Sell at Premium Prices, and I want to Earn Income while I wait;

and to the extent possible, I'll also work to optimize two averages:

My average price per share (the buy low price for the whole investment),

and my average rate of return (the sell high price for the whole investment or any part therein).

This is an enlightened value approach.

And Part 4: I'll create a watch-list and a repetitive analytical and trading process.

I'll use this four-part methodology (strategy) to become a Consistently Profitable Trader (CPT),

thus allowing me to grow my savings at a compound rate of return.

And once CPT status is earned in a longer and easier timeframe,

I'll then work to reproduce these results in the next slightly quicker timeframe,

thus allowing me to realize the best higher rate of return

my skills and the market are willing to yield.

This is another way of stating my Simple Two-by-Four Approach.

Take this seriously.

It's amazing to me how many people come to Wall Street with a video game mentality.

If your primary focus is stimulation and sport,

be prepared to pay a dear price for this form of recreation.

Don't sacrifice a sweet retirement.

Keep it Simple and Straight-forward (KISS);

and never forget the reason we're operating on Wall Street

(e.g., to own a share of our collective economic prosperity in preparation for retirement or whatever),

and not to just pass the time.

Warning: Getting into an investment is easy.

The trick is getting out with a profit,

which generally requires a fair amount of self-discipline and preparation

(to figure out what favorable prices should be),

and the patience to wait for your favorable prices;

which reminds me of a couple of relevant saying,

"There is a time to buy (when we see the right price) and a time to sell,

but most of the time is just a time to sit on our hands

(because current prices are just useless noise)." and

"Hyperactive, Impulsive Trading Is Hazardous to Your Wealth."

You should only be willing to make a trade when doing so puts the odds of success in your favor.

-

If we want to earn an above average rate of return,

we are simply going to have to work for it.

The actual rate of return realized is very likely to be a function of the effort put forward,

where we are on the learning curve, and of course what the market is doing.

This effort includes an iterative cycle of analysis of currently available data,

some trade and investment planning based on the strategy selected,

methodical execution of those plans, and

then some post trade analysis of the results,

which should yield incremental improvements in the process

thanks to our natural ability to learn from our experiences.

All this requires self-disciple, preparation, patience and persistence!

If you're thinking this sounds like too much work,

I'm thinking you're probably right.

Stop here and focus your time and money on a broad-based passive index fund

(like VBINX,

which is a wonderful example of a survivable investment that will pay to hold and that is very likely to see higher prices in the future)

and use the Dollar-Cost Averaging (DCA) strategy,

which at best yields the actual market rate of return,

whatever that is (a positive or negative value) going forward.

DCAing a broad-based index fund also offers the added benefit of allowing you to spend your time on something more enjoyable.

Note that markets can and will go both up and down.

Prices will naturally trade in a broader market trading range.

There will be times when we'll be required to patiently hold an investment that's underwater.

We need to get comfortable with that.

It's simply unrealistic to expect prices to only go up.

There will be times when we'll need to patiently hold an investment that is underwater,

and that's one of the main reason we want to focus on investments that will pay us to hold.

In fact, buying with a value approach (buying low) often results in a near-term loss

because it is very hard to buy the bottoms,

but after a little patience, higher prices often follow.

Alternatively, when using a momentum approach,

we often see a near-term gain,

but after a little more time we often see a loss

because it is very hard to sell the tops.

You might be thinking, "What's going on here?"

If you read on,

you'll see that when the broader market trend is up and healthy (a longer-term momentum approach),

a shorter-term downward price move can actually be to our overall benefit (a shorter-term value approach).

Timing trades near the market tops and bottoms is very hard,

but it can be done in time when one works at it.

It's like learning to surf.

The waves come in off the ocean building a slop on the surface of the water that we ride down and into the shore.

We just need to learn how to mount and ride the surfboard, and then let gravity do the rest.

It will be rare that we'll be able to time these rides perfectly (ride the whole wave),

but we don't have to.

We just need to catch enough to justify the effort,

and therein lies the analogy to learning how to time market tops and bottoms.

We don't have to time the tops and bottoms perfectly.

We just need to get in-sync with the cyclical rhythms,

and then we catch (get) enough of these repetitive movements to justify the effort.

And the best way to start is to learn to time the tides

(the broader market or economic trend),

which take hours (months) to come in and go out.

-

We are going to need a brokerage account to buy and sell stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and other types of tradable securities.

Get the cheapest (low-cost) broker you can find.

I like Charles Schwab,

which bought TD Ameritrade

my prior favorite

because of their ThinkOrSwim trading platform.

I think they have a better set of real-time tools and training materials,

which are all free to account holders.

Note that money spent on trading services and information is money that cannot grow in your account to fund your retirement.

You will also need to Master these Tools of Trade — your broker's user interface,

their online system for investment analysis, trading (buying and selling) and position tracking

(monitoring the value of your individual investments and the size of your account —

I've found that most brokerage interfaces are weak in this regard,

and that it is generally better to use a custom spreadsheet to track and plan these details.

I can give you a simple template to get started;

but you'll need to customize it to meet your specific situation.).

-

One of my rules for retirement planning is Be about the Business of Growing Wealth,

which basically suggests that we need to treat our retirement activities like a business.

We need to be in the business of getting ourselves retired;

and once our Financial Freedom Number is reached,

keeping ourselves in that desirable state

(another one of my rules for retirement planning).

One thing every successful business has is a good set of books.

Bookkeeping is a fundamental part of running any business.

These books allow us to understand our numbers,

our Profit and Loss (P&L) profile,

our expense structure, etc.

Basically, everything a successful businessperson needs to know to properly manage their business.

It's a fundamental truth

that we can't manage what we don't know,

and that we can't truly know something until we track and analyze the details.

-

There are basically two ways to make money on Wall Street:

- Earn a Capital Gain —

A capital gain is realized whenever the proceeds from a sale of an investment exceeds the cost to acquire that investment;

and that's the foundation for the old saying, Buy low and Sell high (or at a higher price).

- Earn Investment Income —

Money can be earned from the ownership of income producing investments.

Examples include dividend income from equity (stocks),

interest income from debt (bonds),

and rental income from real estate investments

(REITs).

These are all examples of being paid to hold;

and over the very long run,

a significant portion (about half) of all market returns are derived from investment income.

Related Notes:

- The sum of these two above is called Total Return.

- Profit and Loss (P&L) —

To calculate our P&L,

simply subtract the value (cash) coming out of an investment from the value (cash) going in.

If that investment paid any income, add that to the value coming out (Total Return),

which we call the Realized or the Current (Market) Value.

When the investment is sold,

it is called a Realized Value;

but while we still own that investment,

we can use the current value,

which assumes that we can sell it now at current market prices.

If the result is positive, we have a profit.

Negative values indicate a loss.

Current or Realized Value = Sale Price X Number of Shares + Income - Costs associated with the trade.

Initial Value = Buy Price X Number of Shares + Cost of the trade

P&L = Current or Realized Value - Initial Value

For example:

We invest $1,000 in ticker XYZ and our broker did not charge us anything to facilitate that trade

(if there was a cost associate with that investment, we must add that to the amount going in).

So, $1,000 is the Initial Value.

When we sold that investment,

we realized a total return of (got back) $1,100,

which included a small fee paid to the system regulators

(a minus cost amount) and a stock dividend (a plus income amount).

Our example profit is: $100 = $1,100 - 1,000.

An alternative simplification is to subtract the Purchase Price from the Sales (or Current Market) Price.

But this simplification does not properly factor in costs or income, as indicated above.

However, this can often be good enough in real-time to quickly gauge an open position P&L.

P&L = Current or Sales Price - Purchase Price

- (Simple) Rate of Return (RoR) —

This is a rate of change in value expressed as a percentage.

This is also known as a (Rate of) Return on Investment (RoI).

To calculate a Simple (or Holding Period) Rate of Return,

we divide the Profit or Loss (cash) coming out of the investment by the Initial Value (cash) going into the investment.

Note that a Simple or Holding Period RoR does not factor in time.

To normalize this for comparison purposes,

we need to annualize this RoR,

which we'll consider below in APR.

There may seem to be two formulas to calculate this Rate of Return

and I show both below.

But they are actually the same formula in two different algebraic configurations,

where the second has factored out common terms to speed up the calculation.

The times 100 at the end of the first formula is there to show the conversion from the resulting decimal to a whole percentage number.

However, it is often left out, like in the second formula,

to reduce clutter because most are able to see the transformation in their heads.

RoR = [(Current or Realized Value - Initial Value) / Initial Value] x 100

Or

RoR = (Current or Realized Value / Initial Value) - 1

Continuing our example from above:

RoR = (($1,100 - $1,000) / $1,000) X 100 = (100 / 1000) X 100 = 0.1 X 100 = 10%

Or

RoR = ($1,100 / $1,000) - 1 = 1.1 - 1 = 0.1 (10%)

- Annualized Percentage Rate of Return (APR) —

To annualize a Simple (Holding Period) Rate of Return,

we must factor in time

by raising that RoR value to the power of 1/n (called the n-th root),

where n is the number of years the investment was held.

Note that we can also do this in days,

but n must be converted to the evaluate factional years

by dividing the number of days held by 365 (the number of days in a typical year).

The formula is:

APR = RoR1/Years

Continuing our example from above and assuming that we held the investment for a year and a day (to get the preferred long-term Cap-Gains tax rate):

APR = ($1,100 / $1,000)1/((365+1)/365) - 1

APR = 1.11/1.00273... - 1 = 1.10.99726... - 1 = 1.09971... - 1 = 0.09971... (about 9.97%)

In the example above I use "..." to indicate these decimal numbers seem to continue without end

(they may be irrational numbers).

Note that if we held the example investment for exactly one year,

the formula above would yield 10% because every value in the exponent is 1 and any value raised to the 1st power is that original value.

- By-The-Way, Market Professionals on Wall Street do have other ways to earn money,

but those activities are beyond the scope of this paper

mainly because they are generally unavailable to the average retail investor.

-

Every trade requires two willing parties,

a buyer and a seller.

Actually, either one of those two parties can be comprised of a temporary group assembled on the fly to facilitate the trade

(e.g., one big buyer wants to acquire, say a, 1,000 shares of XYZ,

gets that order filled (executed) at a trading venue

(a.k.a., an Exchange

or ECN),

by having three smaller sellers grouped together,

say one who wants to sell 750 shares of XYZ, another who has 150 shares to sell, and one with just 100 shares).

Now a days, all this is mostly done by computers, and one or both parties can also be computers too.

Once the trade is executed, the details

(ticker symbol, time of the trade, number of shares traded, and the price)

are recorded as a legal public record

(a.k.a. the Ticker Tape or just the Tape and

Time & Sales),

which can be filtered and viewed by any interested party

(e.g., like on the CNBC Real-Time Ticker).

The only details not recorded on the public record are the names of traders and their brokers;

these are recorded on a private record for regulators and exchange managers to use in their oversight activities.

-

Current prices printed on the Tape

are created by trades between willing buyers and willing sellers,

that presumably both feel that making that trade is to their personal benefit,

tend to be based on a momentary agreement of fair future value.

This may not always be true in every random trade sampling,

but given greater participation

(more trading volume over time) is by definition always true

because most trading volume is from savvy traders and investors

working from a professional trading/investment plan

that is based on professional analysis of the security being traded.

But please note that current prices (trades) may not be rational given the underlying economic realities of the business that issued that security

(e.g., the top of the Internet Bubble in late-2000 and the bottom of the Financial Crash in early-2009,

the prices seen then were not a good indication of value realized just a few months and quarters later).

Never forget that price is not always a good indication of future value;

it is, however, always a good indication of market sentiment, which can be too bullish or bearish relative to likely future value.

Note that we humans have an amazing ability to talk ourselves into beliefs that are not always true.

When market prices become too extreme,

it can pay well to be a patient contrarian sitting on a nice cash reserve — more on this later.

-

There are two basic order types that you will need to be familiar with.

They are

Market Orders

and

Limit Orders.

A Market Order is a request to buy or sell at the best available price as soon as possible.

A Limit Order is a request to buy or sell at a specific price or better,

which may or may not be filled.

Market orders are always filled (executed),

and are used by traders and investors that simply must get in or out of a security position ASAP,

and are willing to accept any price to get that fill.

Buyers using market orders will get their orders filled at the best available Asking Price

(a.k.a., the Ask and Offer Price) when their order reaches a trading venue

in a First Come, First Serve order

(using a FIFO Queue);

and sellers using market orders will get their orders filled on the Bid.

Limit orders are mainly used to advertise a willingness to make a trade,

if the market (someone else) will do that trade at the specified (or better) price.

A limit order can act like a market order

when the limit price is the same as the best available price.

When a buyer uses a limit order that cannot be executed

when their order reaches a trading venue

(because that limit price is below the current Asking price),

that order is added to the Central Limit Order Book (CLOB) as a Bid

using FIFO Queuing,

and will get filled when (if) prices drop through that limit order price.

Sellers using limit orders that are above the current Bid join on the Asking side of the CLOB,

and will get their orders fill when (if) prices rise through their limit order price.

Note: When you hear someone say something like,

"Today there were more buyers than seller." or

"The market was bullish today."

Understand that this means there were more Market Orders to Buy than Limit Orders to Sell today.

On balance, the buyers (the Bulls)

were more aggressive and were willing to accept less attractive prices to get their trades filled

(i.e., the majority of the trading volume today occurred at the Offer Price).

These statements can be confusing to those just starting out and

may be unfamiliar with Wall Street Lingo.

Click here to learn more about the Anatomy of a Trade,

other order types, and how the market advertises price quotes and records trade prices —

a more technical look at the information above.

-

Market prices (trades) for an investable security naturally, and to some degree randomly, trade up and down

based on the supply and demand for that investment

(i.e., the current popularity of that investment).

Buyers create demand by using market orders to force a trade,

and sellers create supply when they use market orders.

When demand is strong, more buyers are using market orders, prices rally; and when supply is abundant, prices decline.

Click here to learn more about Supply and Demand.

All investments naturally go in and out of favor over time.

After every trade, subsequent trades are likely to drive prices either up or down;

and given that follow-on move, one party to that initial trade will look smart and the other, well, not so much.

Understand that the goal is not to look smart; it is to make money over time!

Did you know that both parties to any single trade can actually end up making money

and that both can also end up losing it too?

It's true, and it happens all the time.

Let's not confuse short-term price movement with longer-term wealth creation and destruction.

Just because we have a paper loss now, does not mean we're doomed to end up with a loss;

and just because we have a paper gain now, it does not automatically mean that we'll end up with a bankable profit later.

We cannot control market prices,

and we should not allow ourselves to become giddy when prices move in our favor

and fearful when prices move against us.

Our emotions, if not kept in-check, are likely to cost us a fortune.

We can, however, control what we choose to buy and sell and when we'll do our buying and selling.

We can also choose to only make a trade when the odds favor making a reasonably attractive rate of return.

We need to understand that prices will naturally trade up and down over time because the pros need prices to move,

that's how they (we all) make money,

and if prices will not move on their own,

the pros know how to get prices moving.

But don't confuse that for having control,

the market is just too big and no one has unlimited buying and selling power,

which is the force that drives prices up or down;

but once that excess power is gone,

prices will always revert to their natural equilibrium,

where supply equals demand and where current price reflects the market's collective view of fair value.

Just as a stone tossed into a lake can create a momentary impact on the lake's appearance,

it's not likely to leave a lasting alteration,

especially when that analogy is to the ocean,

which is a much better fit, as the market for most tradable securities is huge.

Finally, we need to also understand that if prices will not move up on good news,

then prices will go down;

and if prices will not go down on bad new,

then prices will go up —

a bit of wisdom understood by seasoned market professionals, and

it's this type of common professional knowledge that makes the statement a self-fulfilling reality.

-

There are basically two ways to hold a position in a brokerage account —

either Long or Short.

Having a long (bullish) position in a security

means that you own the security and are entitled to all the dividend or interest income payments made.

A bull is an investor (a trader) who believes that prices will increase over time and is said to be bullish on or of the security.

To get long a security, an investor (a trader) simply buys the security to open the position;

and the position is closed when the security is sold,

and thus realizes a capital gain when the cost to enter the position is less than the proceeds from the sale.

This is what most people think of when they talk about investing.

A short (bearish) position is the exact opposite of a long,

it's a mirror image of that long position,

and can even be the other side of an opening long trade.

A bear is a trader who believes that prices will decline over time and is said to be bearish.

To get short a security,

a trader must first have the capital to cover the cost of position to avoid margin expenses,

just like a long position.

The only real regulatory restriction on shorting is the need to be in a

margin account

and to be able to borrow the shares for the trade.

Note that some brokers will deny newbies the automatic right to put on a short, but most do not;

and if they do,

just ask them what they need to enable that capability.

In most cases,

to put on a short,

a trader simply selects something like "Sell Short", "Short" or "Short to Open"

as the trade "Type" or "Action" to be performed;

if the trade types "Short" and "Cover" (or something like that) are not included in your list along with "Buy" and "Sell",

then talk to your broker.

Assuming you are able to select "Sell Short" as the trade type,

fill in the rest of the order details,

and then select "Okay", "Review Order", "Preview Order" or whatever your broker's order entry form requires

to get the trade approved before the trade is submitted to an exchange.

If your broker is unable to borrow the shares or there is some other problem with that trade form/ticket,

that trade will be blocked by your broker's system until the problem is fixed.

Don't hesitate to call your broker,

if the problem is unclear or you're unsure about any aspect of this trade type;

they're there to help you

(and if they don't make you feel like that's the case,

find a better broker,

it's a very competitive business).

Assuming all goes as expected and the trade is executed (the order is filled),

the trader thus borrows (from someone who is already long) and sells (shorts) the borrowed security to the market

(to someone else who wants to be long that security or is buying to cover their short)

via their broker's trading interface as a single transaction.

The cash proceeds from the trade are placed in a separate short-sale cash account,

which can earn interest,

and is primarily used to help cover the cost of the closing trade.

It's as simple as that;

and shorting the rallies in bear market can be very profitable.

But please note that being short the security also means that you are also short all the income payments too

(remember, it's the mirror image of a long) —

when an investment makes a payment

(e.g., pays a dividend),

your broker will, without asking, take that payment out of your account and give it to the owner of the borrowed shares.

The short position is closed:

1) when that trader buys back the prior sale (to-cover) the loan, or

2) when the original owner sales the loaned security

(note that your brokers does this automatically,

when the broker is unable to find another long to borrow,

and does not have to ask your permission,

you'll just get a normal trade notification), or

3) when your short position generates a margin call that cannot be met because that position

has gone too far (up in price) against you, causing an excessive loss of value in your brokerage account.

A short position will realize a capital gain

when the proceeds from the short sale exceed the cost to exit (buy to cover) the original short sale.

Because short sales are only allowed in margin accounts,

there are tradable securities that actually go up in price when the underlying investments goes down in value,

like Inverse ETFs,

thus allowing bearish positions in a brokerage IRA.

It's best to keep it simple,

especially when you are first starting out;

just focus on favorable trading opportunities

in the direction of the broader market trend

that are likely to survive and that will pay you to hold,

thus making it easier to become a consistently profitable trader.

There's nothing wrong with going to cash when you turn bearish on your prior bullish position

or when there are no favorable trading opportunities.

Holding cash is a valid (long) position,

it's called waiting for a better opportunity,

which I assure you will come soon enough,

and when it does you'll want to have some cash to take advantage of that new opportunity.

-

The long-term average Market Rate of Return

(according to Prof. Aswath Damodaran at NYU)

of the S&P 500; is about 9% +/- a point or two,

depending on the formula and timeframe you choose to consider.

But note that the actual rate of return in any given year is far more volatile than that average;

it swung as low as -44% in 1931 and as high as 50% in 1933;

and recently we saw a low of -36% in 2008 followed by a number of up years to reach an all new high —

yielding a very nice rate of return for those who owned investments that were able to survive the volatility and

better for those who had cash and were also able to investment

(buy more)

while that market was putting in those scary lows

(trading at super discount prices).

These market extremes seem to happen just a few times in a lifetime

and can be a real blessing to those who understand and are willing to exploit these rare opportunities.

Economically speaking, the stock market rate of return is based on the sum of three or four factors:

- The growth rate

(a positive or negative value) of the business that issued the stock under consideration.

- Plus, the dividend yield

(cash payouts from current operations),

- Plus or minus any change in the market multiple (the P/E),

which is the speculative premium that investors demand for an uncertain future —

When the market feels bullish, P/Es will expand (a risk-on environment);

and when the market feels bearish, the price multiple contracts (a risk-off environment).

- Plus, the rate of inflation

(some text books exclude this from shorter-term calculations,

but it is a real longer-term factor).

A business is basically a money machine.

it will generate sales (the top line revenue figure on an income statement).

A good business will have a revenue figure that excessed the cost to generate those sales,

and the difference is consider profit (the bottom line net income figure).

These profits can then be used to reinvest into new growth opportunities or

some of these can be given to the (stock) owners of the business in the form of

cash dividends,

stock dividends,

stock spinoffs

or stock buybacks.

Businesses that are in growth mode tend to reinvest some or all of those profits in the business.

Growth occurs when consumer demand for the goods or services exceeds the company's ability to meet that demand

and as a result the company hires more worker and/or

gives the existing workers new tools or training thus enabling them to be more productive.

Mature businesses that have already seen their big growth phase and just have a relatively stable demand for their goods and services

attract investors by paying out some of those profits from current operations.

So much the market rate of return in items A and B above

will depend on where in the life cycle the businesses is.

But let's never forget that the actual observed market rate of return is

ultimately based on the market's ever changing consensus view (belief)

about what each of these components is likely to be in the next scheduled report

or some future average thereof.

If you're a short-term trader,

it's all about correctly anticipating the market's view of future value, which is no easy feat.

But we don't have to get all this right to profit from our investments,

we only need to apply my Simple Two-by-Four Approach

and the patience to wait for Mr. Market to show us favorable prices.

-

There is a large body of standardized wisdom about business, economics, finance,

and human nature that can be applied to trading and investing;

and the more we know, the better equipped we become to identify lower risk opportunities to make money on both Wall Street and Main Street.

We do not have to master all or even some this wisdom to make money on Wall Street.

Let's just assume that many, if not all, large institutional investment managers and advisors

(the Smart Money)

have to one degree or another mastered some of this knowledge

and are able to effectively apply it for their own benefit and for the benefit of their investors;

and when they do so, their trades are recorded on the ticker tape for all to see.

Let's also take as a given that we are all creatures of habit,

with a tendency to repeat actives that yield pleasure and to avoid behaviors that cause pain.

It is in fact possible to learn how to see (figure out) what the Smart Money is doing with their money.

We simply need to look at what they are doing, then model that behavior, and then (ideally) figure out why it works.

In time, we can even develop the skill to figure out what the crowd is likely to do next.

It's this last skill, in the author's humble opinion, that is by far the most valuable;

and is an ability that just about anyone can master, given enough time and attention to relevant details.

Just as we can learn to anticipate the behavior of others in our lives,

we can develop a feel for a few individual securities, the group they trade with, and even the whole market

by simply choosing to focus (specialize) on a few market ticker symbols,

which can greatly improve our odds of success.

But even if we can't figure it out, we can still apply the model when we see that it works, and

we choose to avoid activities that do not yield the desired result.

For example, I don't have to understand why hot water comes out of the hot water tap when I turn it on,

I just need to know that turning that knob yields hot water and the other cold.

Understanding why this works can help me fix the problem when expected results fail to materialize.

We'll take a closer look at how we can see what the Smart Money is doing and why in subsequent paragraphs.

-

We can use simple statistics

to understand and draw profitable insights about economic and market data.

One of the easiest ways to analyze these data sets is to

plot or graph the data on a histogram

or chart over various timeframes.

Seeing how the data evolves (and in the case of economic data, is revised) over time can give

us real insights into what is happening now;

and once we learn some of the following relationships,

we are better equipped to predict what is likely to happen next,

and that is a huge advantage when it comes to investing for our future

(check out the book

The Visual Investor, by John Murphy).

A price chart is a specific example of how we can analyze trades (market data) recorded on the ticker tape

(we'll learn a lot more about this later).

Although it helps

(check out the Khan Academy's Statistics and Probability),

we do not have to master statistics to find lower risk investment opportunities;

we just need to understand that our brains are very good at finding exploitable patterns in familiar data

and that coupled with the knowledge that some of the data exhibits the following tendencies:

- Some data (both economic and market) have a cause and effect relationship and/or simply tend to show-up together

(i.e., the data has a dependency and/or a correlation)

meaning that if we see one thing, we're likely to see the other thing too.

- The data can be analyzed in various sample sizes

(e.g., timeframes) and these groupings can help us better understand what is likely to happen in the future.

For example, larger sample sizes (more data) tend to be more meaningful than smaller sample sizes.

We can use information from the bigger (slower) samples to exploit aberration in smaller (quicker) samples.

- The data tends to trend (generally move upward, downward, or sideways) in every sample size (timeframe).

A sustainable (fundamentally well founded) trend is likely to continue, and

an unsustainable trend is likely to reverse

(because it has gone too far and is no longer representative of the fundamental forces

driving the broader trend as seen in bigger samples sizes).

- The data tends to cluster (average) around a trend line

and the distribution (the spread or width) of the data indicates the range and nature (tendency) of sample data.

Most economic data and market prices tend to have an almost

normal distribution

(a bell shaped tendency),

meaning that most of all future readings are likely to fall within

three standard deviations.

However, it is important to understand that there can also be some occasional extreme events, deviation away from the mean.

But those extreme deviations tend to be very short lived.

Assuming that there are no real and prolonged changes in the underlying forces driving the data,

which is almost always the case,

the new distribution will return to the prior or some new normal distribution mean

that is very likely to resemble the prior data signature.

To be technically correct,

researchers have found that virtually all market prices have a

log-normal distribution,

and it is their rates of return that have a normal distribution.

Note that a normal distribution can have some negative values,

but it is extremely rare, if not impossible, for market prices to become negative.

I've found that if you focus on survivable market indices and blue-chip investments,

both their market prices and their rates of return have an effective normal distribution

with some fat tails.

Or simply put,

don't be surprised to find that the future tends to generally resemble the past

when it comes to investing in securities that are backed by large and mature economic forces,

and don't be surprised when their prices occasionally go to trading range extremes

before returning to a broader average.

- Related data can be analyzed using different statistical techniques

and that allows us to see a divergence in that data,

which make it easier to see if the underlying forces driving a trend or clustering are

still supporting the current pattern or signaling a change

(a good time to go to cash and/or prepare for the next likely pattern).

-

Past data can show us what is possible,

the nature of the data

(everything above),

and the historical odds of various events in the past,

which can be a very useful guide for the future.

But we should never assume the future will always be like the past.

It's true that what has happened in the past tends to generally happen again in the future.

But never forget that every moment in the future is unique and anything can happen.

We need to also consider the odds and consequences of the unlikely occurring

(think, what will I do then?)

because every once and a while

(and especially when we're learning)

the unexpected happens

(and then we're forced to test the effectiveness of our recovery plan).

As traders and investors,

these insights are worth a fortune to those who can learn to spot and play these naturally reoccurring patterns in the data

as they give us an exploitable edge (i.e., put the odds of success in our favor).

We simply need to learn to think in terms of probabilities,

learn which groups of data have a dependency and/or a correlation,

and then to only put our savings at risk when we're more likely to realize an attractive risk-adjusted rate of return.

Investing time to master these Quantitative skills

will surely yield a very impressive rate of return.

In the authors (not so) humble opinion,

the statistical wisdom identified in this paragraph may well be the most valuable information presented in this paper.

However, this statistical wisdom can only be as good as the data and the methodology surrounding the analysis.

Given that,

I recommend Annie Duke's book

Thinking in Bets and related YouTube lecture.

Annie talks about learning how to make good decisions in the face of uncertainty,

to be a proper truth seeker and to be data driven.

She advocates objectively seeking all available information and using that to make decisions,

and then learning from the experience.

Do more of what puts money in your pocket and less of the alternative.

-

"What are the odds and what's the risk?"

In a number of points above I've referred to understanding the odds and not taking on too much risk.

But how can we know the odds and risk?

Truth be told, we can never know the future for sure.

However, on Wall Street many professionals and amateurs alike use simple statistical (quantitative) analysis

of prior performance as an indication of likely future odds and risks

because the future tends to be much like the past (variations on a familiar theme).

If we use enough historic data

(applying the Law of Large Number),

we can get a good feel for what the odds and risks were in the past.

We can then use this data to project into the future

with the clear understanding that anything that is possible can still happen and sometimes does,

and we need to factor all that into our plans.

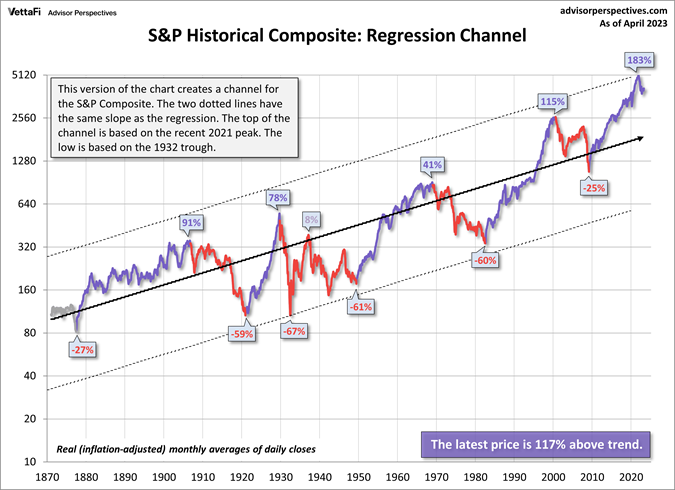

We can use a Monthly Chart to better understand the historic possibilities

(BTW: If your investment or the index that it is designed to track cannot fill a Monthly Chart,

then it may not be a survivable investment,

which breaks my Simple 2-by-4 Rule #2 above.).

Furthermore,

we need to understand that this historic data

is pretty much unreliable when it comes to saying exactly when something is likely to happen,

but it can be very reliable about what can happen again,

given enough time and

assuming a little common sense and maybe some of the wisdom in the paper.

We can use this historic information to make informed choices about the best way to invest our time and money.

It's one good way to play to favorable odds and avoid unacceptable risks.

If you feel that you do not have the time (or talent) to do all

this historic market research,

refer to Ken Fisher's snarky book

Markets Never Forget

where he and his team have done the work and documented the results.

Once we have a good understanding of the historic odds and possibilities,

we can then sort the alternative possibilities into three basic categories or scenarios:

The first are those that are unlikely, but do happen and are very costly when they happen.

These are what low-cost insurance was designed to address

(e.g., your house burning down),

and some on Wall Street will say that buying cheap

Put Options is like buying insurance for your portfolio.

But I know from first-hand experience that when it comes to trading and investment choices that need put protection,

it's best to just avoid these or do this through funds that are run by manager(s) that have a track record of success in this area.

The second are those alternatives that are likely (are frequently seen on longer-term charts) and have favorable risk/reward profiles,

and these should receive the bulk of our time and capital.

Look for trading and investing opportunities that will pay off when these alternatives do show up again

(e.g., those opportunities that adhere to my Simply 2-by-4 Approach and that I talk about below).

All other alternatives are just not worth much time or capital

because the odds say when these likely event do happen the risk and the reward are both minimal (just no big deal)

or alternatively are just so unlikely and if they do ever happen we've got much bigger problems than our savings

(e.g., The economy (the whole market) or a major sector will crash and never recover, this has never happened —

Note that there have been some individual businesses and a few smaller groups of similar businesses that have failed and never recovered,

but those failures actually fall into the first category above,

which need to be avoided or played through diversified mutual funds).

Like Ken Fisher and his staff,

many professional investors use a rigorous fundamental analysis of the businesses and the associated supply-chains that

they specialize in to firm up their understanding of what is likely to happen and all that goes into their estimates of likely results,

and thus guides their actions in the market.

We can use charts (called technical analysis) to see what the big (smart) money is doing (more on this later).

It's called the Wisdom of Crowds,

which are amazingly correct most of the time.

This, of course, does not guarantee future results.

We can use historic chart patterns to look for repeatable and predictable behavior.

Once again, we can't always know when a pattern will happen,

but we can know that it can happen sooner or later based on historical odds.

We should focus our attention on investments that are backed by

large, mature businesses (e.g., members of the S&P 500)

because they support a high degree of predictability.

Having a reasonably good and long business track record

(the Law of Large Numbers)

is a great way to get a feel for likely future odds

and is also a good way to reduce risk.

Given that data, we can use quantitative techniques

(statistics, as suggested above)

to firm up our understanding about a specific investment,

the business backing that investment, and all the competitive alternatives.

On Wall Street, these quantitative measures show the historic odds

and the distribution (the spread) of these reading are a measure of the variance (a.k.a., volatility),

which The Street likes to call The Risk.

So, on Wall Street the odds and risk are just an example of applied statistics.

And now for a Main Street perspective:

I, like many others, prefer to view risk not in terms of volatility,

like many on The Street,

but in terms of a permanent loss of capital,

a Buffett like perspective.

I actually see the prior view

(volatility equals risk)

as a confusing and misleading definition